Launch talk for Jill Jones' Ash is Here, So are Stars

at Sappho's Wine Bar, Glebe, Sydney

13th November 2012

This is the praise-the-poems section of the evening. We're going to welcome into the poetry sphere, Jill Jones' latest book - published by Ralph Wessman at Tasmania's Walleah Press.

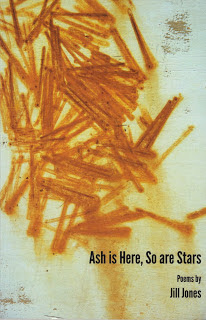

It's called Ash is Here, So are Stars and, regarding the cover, it looks like there could be some rust as well. The cover image is Annette Willis' photograph of macro-rust in Marrickville.

On her dot com page Jill says her poems are "fragmented, flagrant, floating - perhaps an abstract or ruined lyric, where ‘I’ has shifted from the centre."

She says she has "a continuing interest in texture, pattern and transience, of jumping in the midst of the flow, experience in language underway, asking questions about how the pieces don’t fit as shards alter meanings." She continues "While not getting hung up on ‘the image’ as such, I’ve always worked visually. I’m not interested in telling images what to do but rather a process of seeing. The soundings of a poem are also important to me, as is the way the line works. I prefer more linguistic play in the line emphasising both connectedness and parataxis, the flexing of thought/meditation and critique, including self-critique."

Phew. That kind of covers everything. I think perhaps that makes me redundant for this task. What should I say? Usually when I make these speechettes I try to explicate the poems for you so that you'll be interested in reading the book and, of course, so that the poet gets some kind of rewarding warmly glowing feedback, but Jill's said most of it herself in those little extracts from her web page.

Anyway, you get the idea - she places emphasis on both gaps and spaces and actual connected or meaningful text. These poems are also mostly more observational than involved. There are many allusions and there's the impression that the poems' different or separate elements have been picked up and put together like a gleaner's collection of bric-a-brac. In the second poem here, 'Give Yourself Up', the reader begins to see what kind of effort is going to be required in reading this collection. There are disjointed, disrupted sentences; phrases, which are like lists of activities or things, that have a number of letter spaces separating them, replacing conventional conjunctions or where others might use line-breaks - so making the 'parataxis' Jill talks about on her web page. I'll try to read a few lines - as they sound or appear on the page -

if I could make it happen light it

up my hand breathe smoke back its direction

I could discuss theme tunes to me beating hands on skin

There's a Jo Burnsian line in the same poem - 'what's the point of/sadness among tax cuts' and later in another poem there's the Burnsian alliteration in 'legal action, legislative lugubrosities'.

On the back cover, I mention 'projective poetry' that began in the 1950s in the US. The Black Mountain poets used what they called 'open field' composition to replace traditional closed poetic forms with an improvised form that should reflect exactly the content of the poem. And the content was one perception directly followed by another perception. The form was based on the line, and each line was to be a unit of breath and of utterance. Jill relates very many instances of breath and breathing in these poems, but now I think that perhaps their effect is to draw attention to projective verse rather than practise it; they are "about" breath rather than its application.

One poem that has elements of combined Ashbery/Tranter/JoBurns, (yes, that is a heavy combo) is called 'Negative Breathing' -

Maybe I was born among democracy among libertarians

on the lam. Maybe I was carted with mimics & homeopaths

to the tune of a trice bawdy ballad as exchange.

The 'maybes' set that poem's course. Jill's poetry often wonders about its own location and its connotations as a made thing, often self-consciously examining its own process. One is even called 'Whose Words Did These Things?'

The reading experience can sometimes seem a bit like being in a maze that has many short directional changes. The reader, once adjusted to the unusual or particular use of language and the broken and absent grammar in these poems, will appreciate their energy. There are odd, often wacky, juxtapositions where nouns or conditions act in unexpected ways - 'time goes flaccid', 'Travel/rain fleet marks', 'a new treatise flip-flops in the marrow','kitchenette lyke as much madness/no, no, go obscurely yet',

'lyke' is spelled 'l-Y-ke' - which brings me to mention the use of archaic (sometimes arcane) words - in 'Southern' - 'grizzling bairns naught in pocket a little/nickel maybe the brass gone into glass' to describe a poor childhood, a drunken father - it's like rewritten Dickens. Some reclamation is going on too - 'among the bane/written on the window','it frets and comes fullest 'til it breasts/yes, you know how it breaches anew though/it's old' ; there is yoghurt that is 'yawed', and so on.

Jill's multiplicity of approaches are unbounded. There is variety in the shorter standalone poems and then there's 'My Fugitive Votive' - a sequence of experimental sonnets and a long fragmentary poem, 'Where we Live', closes the book.

For an instance of the material intensities mentioned on the back cover and the materiality of the cover image - there's rust in a painterly, moody poem called 'Scratchings, Rust'-

A canvas of anxiety

inscribes walls

and metal

where birds

and people go over

paving and crossings.

much is overwritten.

Much disappears in

telling the hours

Rust acts to slowly alter and transform and disappear.

Sometimes there's a nonsense poem like 'Brilliant Slippy Works' that seems kind of 'Edward Learesque". It's a poem about theft.

'A Moon Song' is the most conventional poem in the book -

Sometimes the town needs to be silent

Let its secret crows sing, however

They carry changes

The moon's white eye closes on the horizon

Leaves accompany us along the road

My fingers feel out the cold on the gate

There's more night now and perhaps more time

Jill Jones' poems don't arrive fully located or grounded, they are instead anticipating possibilities - everything is potential and in an abstract kind of state. It's through obliquity that the poems seem to desire an un-knowing; to unlearn, to find a kind of relief from the weight of contemporary poetics and from centuries of tradition. Mostly, things here are tangential.

The final lines offer another possibility

voices

might break light

Return to Extras - selected writings or Pam Brown's web site.